Showing posts with label psychology. Show all posts

Showing posts with label psychology. Show all posts

Friday, May 26, 2017

The Ugliness Penalty: Does It Literally Pay to Be Pretty?

There are economic studies that show that attractive people earn more money and, conversely, unattractive earn less money. I’m pretty sure that I’ve heard something along those lines before, but I had no idea they were called the “beauty premium” and the “ugliness penalty.” How wonderful and sad at the same time. But while these seem like pretty commonplace ideas, there is no real evidence as to why they exist. A new paper published in the Journal of Business and Psychology tested three of the leading explanations of the existence or the beauty premium and ugliness penalty: discrimination, self-election, and individual differences. To do this, the researchers used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health. This is a nationally representative sample that includes measurements of physical attractiveness (5-point scale) at four time points to the age of 29. People were placed into 5 categories based on physical attractiveness, from very attractive to very unattractive. They statistically compared every combination they could think of and came up with many tables full of tiny numbers, as well as some interesting results.

Discrimination

It is what it sounds like: ugly people are discriminated against and paid less. And it isn’t just from employers, it can also be from co-workers, customers, or clients that prefer to work with or do business with pretty people. Or it could be a combination, like an employer that hires someone pretty because they know that others will respond to them better. Because there is a monotonically positive association between attractiveness and earnings (an overly academic way of saying that one is linked to the other), it can be tested.

The results painted a somewhat different picture than you might expect. There was some evidence of a beauty premium in that pretty people earned more than average looking people. However, the researchers found that attractiveness and earnings were not at all monotonic. In fact, ugly people earned more than both average and attractive people, with “very unattractive” people winning out in most cases. So no ugliness penalty and no discrimination there. Good, we don’t like discrimination. Rather, the underlying productivity of workers as measured by their intelligence and education accounted for the associations observed. Basically, ugly people were smarter (and yes, IQ was a variable).

Self-Election

This occurs in the absence of discrimination. A person self-sorts themselves into an attractiveness group based on how attractive they perceive themselves to be and may choose their occupation accordingly. If a pretty person chooses an occupation that has higher earnings (or vice versa), then there is a positive association between attractiveness and earnings both across and within occupations.

Once again, the results were unexpected. The self-selection hypothesis was refuted. Ugly people earned more than pretty people. In fact, very unattractive people earned more than both regular unattractive and average looking people. This is where the researchers start calling this effect “the ugliness premium.” Good term.

Individual Differences

This one posits that a pretty and ugly people are genuinely different. Try looking at it in the context of evolutionary biology. Physical attractiveness is based on facial symmetry, averageness, and secondary sexual characteristics, which all signal genetic and developmental health. Many traits can be quantified very accurately with today’s computers. There are standards of beauty both within a single culture and across all cultures. Studies have also shown that attractive children receive more positive feedback from interpersonal interactions, making them more likely to develop an extraverted personality. If health, intelligence, and personality, along with other measures of productivity, are statistically controlled then attractiveness should be able to be compared to earnings.

Again, there was absolutely no evidence for either the beauty premium or the ugliness penalty. Rather, there was some support for the ugliness premium. Now keep in mind, this was not as much a this-higher-than-that, but more of a this-different-from-that type of hypothesis. So there actually is strong support that there are differences. There was a significantly positive effect of health and intelligence on earnings. Also, the “Big Five” personality factors – Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (or OCEAN…cute) – were significantly correlated with physical attractiveness. Pretty people were more OCEA and less N. This may be why looks appear to have an effect on earnings.

Overall, not what you thought it would be, huh? Me either. The importance of intelligence and education as it correlates with attractiveness would be an interesting next step. I wonder if it reflects the time at which these data were taken. We are seeing the Rise of the Nerds, where intelligence is outpacing beauty in terms of success. Had they analyzed data from another decade, would the ugliness penalty find support?

Kanazawa, S., & Still, M. (2017). Is There Really a Beauty Premium or an Ugliness Penalty on Earnings? Journal of Business and Psychology DOI: 10.1007/s10869-017-9489-6

image via Linked4Success

Saturday, February 13, 2016

Where Are My Chocolates?: The Role of Gift Giving on Valentine's Day

I think that the day after Valentine’s Day is actually the best. After all, chocolate is 50 percent off. However, using the holiday as an excuse to delve into the myriad of studies that attempt to explain the complexity of human attraction and relationships is pretty fun. Last year I examined moves, specifically some fly dance moves and rather cheesy pick-up lines. Today, I think I’ll explore gift giving.

In the field of animal behavior, gift giving (or nuptial gifts) is practically its own subdiscipline, particularly in insects. These gifts are typically food items (but sometimes are inedible tokens) presented from the male to the female during courtship. They may be to show the female that he is worth her time, show how healthy the he is, how good a provider he can be, or simply to keep her distracted from eating him during the actual mating (except in those cases of specialized body parts or “suicidal food transfers”…now that is the ultimate sacrifice for your bae!). The gift giving behavior, especially if it involves an extreme sacrifice on the part of the male, can only arise if the giver has some net fitness benefit. He must be able to increase his paternity share (particularly in polyandrous mating systems) and/or boost the female’s fecundity, thereby increasing the number of offspring.

Humans are not insects. Obviously. But gift giving, and many of its underlying behavioral mechanisms, is still very important to our mating system. I’ve already mentioned chocolate that, while offering little nutritive value, sure does make us ladies happy. As you know, these are not the only gifts given on Valentine’s Day. An interesting paper by Rugimbana et al., published in the Journal of Consumer Behavior in 2003, examines the role of gift giving on Valentine’s Day. The authors point out right up front that if you think about this “holiday,” you might notice that it is rather small in scale compared to the high rollers (i.e., Christmas). However, it is unique in that it has become almost ritualistic in its symbolic gift giving. So much so that it has become over-commercialized and now causes increased anxiety and pressure to those who involve themselves in it. The study looks at the role of social power exchanges as the basis for gift giving on Valentine’s Day, specifically in young men. To assess this, they interviewed male participants aged 18-25, asking about their attitudes towards Valentine’s Day, perceptions of female expectations and various types of gifts, and the appropriateness of various types of gifts to the length of a relationship.

This study found that for young men “the overwhelming motive for [giving] gifts on Valentine’s Day was obligation.” The men thought that gift giving was necessary when in a relationship simply because their significant other was expecting it. How romantic. This obligatory gift giving was thought essential early on in a relationship, especially if they wanted to avoid a conflict. The phrases “all hell would break loose” and “I hope…I’d still have a girlfriend” were used. However, only 25 percent of men replied that they expected something in return for the Valentine’s Day present. That sounds a bit harsh. But not so fast. When the researchers broke things down by their altruistic value, or lack of, some interesting patterns emerged. For example, when men were asked “if you were to buy lingerie for your partner, would it be for you, or for her?,” 90 percent said that it would be for themselves. Shocker on that one, I know. That isn’t to say that altruistic answers weren’t given (e.g., “you don’t need a day to say I love you”), just that it is difficult to separate from self-interest (e.g., “if you do it right, you’ll be glad”).

The authors were able to boil Valentine’s Day gift giving down to three motives: 1) obligation, 2) self-interest, and 3) altruism. Importantly, these motives existed in combination and a “social power exchange” was present. In other words, giving rewards the giver. All of this sounds rather callous and almost Machiavellian. Ladies, we sound rather demanding…I mean, “all hell will break loose” over one day and one gift? Wow. And guys, while turning an obligation into a reward is rather cunning and evolutionarily arguable, it is also sort of cliché at this point. Perhaps both sexes should consider the gift giving rules of other holidays like Christmas. Just a thought.

(image via Valentines Day Pictures)

Labels:

behavior,

holidays,

humans,

psychology,

Valentine's Day

Thursday, February 12, 2015

Will You Be My Valentine?: Making All the Right Moves

My Valentine’s Day themed posts have been both popular and fun to write. In last year’s Getting a Date for Valentine’s Day series, you learned that you should wear something red, gaze without being creepy, tell a good joke before walking up to your potential date who is preferably standing next to some flowers, and then open with a unique request to segue into asking them out. But that isn't the end of the story. Oh no, there are many more things that you can do to attract that special someone, all scientifically examined of course. Today we’ll take a look at two more of them.

Bust-A-Move

It’s serendipity that our V-day themed discussion about sexual selection starts on Darwin’s birthday (Happy Birthday Chuck!). Did you know that Charles Darwin was actually the first to suggest that dance plays a role in evolution? It is a sexually selected courtship signal that reveals the genetic or phenotypic quality of the dancer, usually the male. Basically, the quality of the movement signals things like physical strength and fluctuating asymmetry (FA). The latter is a term you see a lot in these types of studies and it describes how much an organism deviates from bilateral symmetry. Essentially, if you develop all lopsided then it will show in your movement. Take what you know of testosterone, or other steroids. Increase that and you see improved physical strength and athletic ability. Now translate that, and its developmental implications, to dance.

It has been suggested that human women have developed ways to assess these visual cues in men in order to select high quality mates. However, quantifying these decisions in a study has proven difficult as women use the appearance of the dancer as well as their quality moves. A 2009 study by Hugill et al. in the journal Personality and Individual Differences looked at whether male physical strength is signaled by dancing performance. They included 40 dancers, recorded their age, body weight and height and then gave them a series of handgrip tests to quantify their physical strength. Then they dressed the men all in white overalls (I know, sexy right?), put them in a blank grey room, and asked them all to dance alone to the same song while they were being video recorded. Let’s assume, for the sake of this argument, that this scenario doesn’t induce awkwardness in these men. Then each video was converted to grey-scale and a blurring filter applied to cover information about body shape. Once this prep work was done, the researchers recruited 50 female to rate each video. The results showed that the women perceived the dances of physically stronger men as more attractive.

The rise of motion-capture technology has added a very useful tool to this type of study. Rather than going through all of those post-conversion video steps, complex movements like dance can be captured by the computer sensors to be applied to homogeneous human figures. A 2005 study by Brown et al. in Nature did just this to look at the variation in dance quality with genetic and/or phenotypic quality. They motion-captured 183 dancers and selected 40 dance animations based on the composite measures/level of fluctuating asymmetry of the dancer (hmm…I wonder if they could get Andy Serkis to help out). Then they showed these dance animations of symmetrical and asymmetrical individuals to 155 people (themselves characterized for FA) to rate. In both males and females, the results showed that symmetrical individuals were better dancers, with males better than females, but sex didn’t matter within the asymmetrical group. For the raters, generally males liked to watch female dancers rather than male (you’re shocked, I can tell), and females liked symmetrical males. Data also showed that female raters, more than male raters, preferred the dances of symmetrical men, and that symmetrical men prefer symmetrical female dancers more than do less-symmetrical men. If you have ever interacted in any social context ever then you know that beautiful, good dancers liking beautiful, good dancing partners isn’t exactly groundbreaking. But what does this study mean for the hopelessly asymmetrical? Shift your preferences downward to a less symmetrical potential date.

Now the question becomes about the dance itself. Which body movements are the attractive ones? A 2010 study by Neave et al. published in Biology Letters looked at specific movement components within dance to see which one(s) influenced perceived dance quality. Using motion-capture, the created digitally dancing avatars of 19 men for 37 women to rate for dance quality. To quantify specific movements, angles, amplitudes and durations of joint, angular and unidirectional movements were measured. Good dancers were those that had larger and more variable movements with faster bending and twisting movements in their right knee. Weirdly specific, right? Especially that right knee thing. But, considering that most people are right-handed, this might be expected.

So what have we learned? Well, we now know that how you move tells someone a lot about you, regardless of how attractive you are. Maybe a good dance class is in order?

Hey baby, you must be gibberelin, because I'm experiencing some stem elongation.

You've got your eye on someone fabulous. You walk over; lean against the bar and…

What you say next can make or break that first meeting. What do you say? There are several studies out there that look for practical answers to this question. Considering our current dating discussion, we’ll hone in on pickup lines (or chat-up lines), which run the gamut from cute to cringe-worthy. In general, these types of studies ask “What makes a pickup line good?”

To get at this, many categorize them according to a 1986 study by Kleinke et al.:

- Cute-flippant – convey interest with humor that is usually flirtatious or sexual

- “You must be tired, because you’ve been running through my mind all day,” (A line that has actually been used on me. Sigh.)

- “Do you have any raisins? No? Well then, how about a date?”

- Innocuous – convey interest without incurring the pain of from potential rejection by using simple questions to start conversations

- “Have you seen any good movies lately?”

- “What do you think of the band?”

- Direct – convey interest with sincerity and flattery

- “I saw you across the room and knew I had to meet you. What’s your name?”

- “Can I buy you lunch?”

Okay, so now we have zeroed in on the categories that work best: innocuous and direct. But is there something about the lines themselves that make them successful? A 2006 study by Bale et al. aimed to construct a pencil and paper instrument to index the effectiveness of pickup lines and identify cues as to their effectiveness. To do this, they created 40 vignettes in which a man attempted to start a conversation with a woman including 20 “one-liners” chosen as signals of particular male traits. Then participants were asked to rate the man’s pickup on whether or not a woman would continue the conversation. As with the previous studies, pickup lines involving jokes, empty compliments and sexual references rated poorly. Lines that indicated those evolutionary desirable traits did best: generosity, cultured, and physical fitness.

A 2007 study by Cooper et al. built on the Bale et al. work, looking at the effect of personality on the response to pickup lines. This study proposed that these openers can have two functions: attraction and selection. These functions may allow men to increase their effectiveness by skewing the distribution of women they attract towards a particular personality type. The researchers used the short scale version of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised (EPQ-r) to measure the personality traits of the participants. They also asked the participants to complete a Dating Partner Preference test which asks them to rate 33 adjectives to show how they felt about the trait in a prospective dating partner. Generally, they found four groups of adjectives that were preferred: good mate, compliment, sex (preferred by males), and humor (preferred by females). Are you sensing a theme yet? They also combined their dataset with Bale et al. to establish the relationships among vignettes to explore the effect of the sex of the participant. Women rated humorous items more favorably and sexually loaded lines less favorably than did men. (Again, you’re shocked, I know.) However, it turned out that men underestimated some things; like when he revealed wealth or proffered help in a way that showed off his character and when he handed over control of the interaction to the woman. On the flip-side, he also overestimated how she responded to showing off his accomplishments, especially if it was laden with innuendo.

Lessons learned from this? Construct your pickup lines carefully. Sure, humor is important but in pickup line form it just makes you look like an idiot. Instead, ask her what she thinks, listen and respond intelligently, and talk about yourself without being a show-off. In short, be a normal person, not a weirdo.

(images via How Stuff Works, BuzzFeed, and QuickMeme, respectively)

Labels:

holidays,

humans,

psychology,

sociology,

Valentine's Day

Friday, December 12, 2014

The White Elephant in the Room: The Gift of Subversion

Ah, the holiday work party. Free food, spending time with people you spend your whole day with already, and enough boozy libations to make things a bit more interesting. Here in North America, many workplaces engage in the gift “game” called the White Elephant Gift Exchange. On this topic, I'm basing today’s post on an article that I recently came across by Gretchen Herrmann in The Journal of Popular Culture where she dissects the Machiavellian nature of this little holiday game.

The White Elephant Gift Exchange (that I’ll abbreviate to WEGE, which you are free to pronounce as ‘wedgie’ even though no one does) is a pastime aimed to upend our normal conventions and beliefs of holiday generosity by celebrating and subverting the materialism. The goal is an unleashing of entertainment and satire, made all that much better after the first glass or two of eggnog.

I've written before on the topic of the perfect gift, concluding that considering someone’s interests and getting them something that you know they will love and use is the way to go. Herrmann generally agrees on this conclusion, pointing out that the ideal gift is a special item that is imbued with personal sentiment. This special item carries with it an emotional attachment that transcends the obligatory reciprocity of typical gift-giving. But object of the WEGE is exactly the opposite of all of that.

Actually, the name WEGE can vary depending on the type of gifts. The specific version of the game typically goes after a particular brand of holiday subversion: shrewd trading and parsimony (e.g., Yankee Swap, Scotch Auction), undercutting holiday beneficence (e.g., Dirty Santa, Evil Santa), turning Christmas on its head by those that are considered inscrutable and untrustworthy (e.g., Chinese Christmas, Chinese Gift Exchange), pointing to the dubious value of the gift or that it might be pre-owned (e.g., WEGE), and/or telegraphing personal gain at the expense of others (e.g., Stealing Santa, Rob Your Neighbor, Cut Throat Christmas).

Basically, the rules are these:

- Participants bring an anonymous wrapped gift that fits within prespecified guidelines (price, regifting, etc.) that they slip into the gift pile.

- Everyone picks a number that is used to determine the gift-choosing order of the participants.

- First Turn: The first person called chooses a gift from the pile, opens it, and then displays it to the other participants.

- Second Turn: The next person has three choices. They can either a) steal the gift from the first person, sending them back to the gift pile for another, b) select, unwrap and keep a gift from the pile, or c) select and unwrap a gift from the pile and swap the unwanted gift with the first person.

- All Subsequent Turns: Each new person can steal any unwrapped gift or choose a wrapped gift from the pile. However, a gift can’t be stolen more than once during a turn, and a particular gift can’t be immediately stolen back from the participant who just stole it.

WEGE it isn’t about the personalization, it’s about the stealing. The Machiavellian nature of the game is spelled out in its stealing, its taking, its greed. Rather than the generosity of the personalized, perfect gift, the emphasis is placed on personal gain, creating a series of winners and losers, and getting something for nothing with impunity at the expense of another. I think we can all agree that that is what makes it fun.

You want to make sure that you bring a gift that will engender group favor and can trigger a chain reaction of stealing and hilarity. For example, one of the most popular gifts I’ve seen at one of these events was a big battle axe. Yeah, a real one. How many times it was stolen = funny; who actually wanted a battle axe for their very own = hilarious. In other years, the same group went crazy over gifts like a big stuffed moose or a case of craft beer (I ended up with that one!). So is there a key to picking out the perfect gift for one of these events?

First is to consider your group. Do they appreciate the tacky, silly, and weird or are they more the classy, mainstream crowd? However, slipping a bizarre gift into the latter crowd’s pile will likely cause unexpected amusement. Second is to keep to those prespecified rules. Don’t spend a lot of money trying to impress people; keeping to the anonymity means they won’t know it was you anyway. Next is to not forget the creative wrapping and use it to satirize as well – although you might have to be equally creative to keep it anonymous as you walk into the party.

Herrmann explores the transient nature of both the receiving of the gift and your attachment to it. In the game, the gift itself can be arbitrary and that participants are forced to focus on the transience of possession instead. She cites behavioral economists who describe the “endowment effect,” wherein the brief possession of an item makes it worth more to the owner than other identical items. This extra value makes the stealing of this item even that much more poignant. However, she also points out what we’ve all heard during particularly rousing games: “Give me that! I want it!” so there is at least some value of the item too.

Herrmann breaks down the gifts into three categories:

Fetishized Commodities: Those items that are disproportionately coveted and stolen. My battle axe example is a good one. These gifts take on a life of their own as they gain more value every time they are stolen. A hierarchy of items can emerge as the game goes on. Within this hierarchy are also a series of substrategies like pointing out other gifts to take attention away from yours, loudly hawking lousy gifts in the hopes of trading up, sitting low and hopping no one will see and remember what you have, or even making after-game deals.

Booby Prizes: Of course, no one wants to end up with the “booby prize” or gifts at the undesirable end of the hierarchy. So much so that often the rules will stipulate that the final recipient must take it home with them. It can sometimes be difficult to predict whether a gift will be seen as a booby prize. Perhaps the battle axe was originally meant as a booby prize, a way offload an old D&D costume. But bad became good.

Lazarus Gifts: These are the items that make reappearances in coming years. They are the ones that are most commented on, laughed about, or pawned off. These resurrected gifts actually add to the layers of complexity and amusement of the WEGE.

Ultimately, the WEGE is about group bonding through entertainment. Perhaps that’s why it is so often played at workplace parties. There’s a ritualistic swapping of gifts, but you don’t need to go through the stress of finding the perfect gift. So this year, think of a creative, subversive, fun WEGE gift. Oh yeah, and don’t forget to steal all those good ones away too!

M. Herrmann, G. (2013). Machiavelli Meets Christmas: The White Elephant Gift Exchange and the Holiday Spirit The Journal of Popular Culture, 46 (6), 1310-1329 DOI: 10.1111/jpcu.12090

(image via The Lovely Journeys)

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

The Final Girl: The Psychology of the Slasher Film

Halloween has put me in the mood to talk about slasher movies. Once I got to looking around, I found more papers on the topic than I thought I would. I gotta warn you, this is a long read, so grab some popcorn and settle in for some slasher movie fun.

If you are a fan of horror films then you know Randy Meek’s “Rules that one must abide by to successfully survive a horror movie”: (1) You can never have sex…big no-no, sex equals death, (2) you can never drink or do drugs…it’s the sin-factor, an extension of number 1, (3) never, ever, under any circumstances, say "I'll be right back" ‘cause you won’t be back. Scream got me to thinking about the psychology and tropes of the horror movie (don’t worry, this post is spoiler-free). Today I’m going to focus on journal articles and so won’t take the time and space going through the history of horror films (there are a list of good links below).

I used Scream (1996) as an example because it is one of those movies that both parodies the genre and, at the same time, becomes an entry within the genre. That’s tough, and when done well, really great. In Scream’s case, it also resurrected a dormant genre to a whole new generation, the Gen Y teens of the 90’s (including me). In 2005, Valerie Wee published a paper in the Journal of Film and Video that looks at the role of this movie, and its sequels. She redefines and labels a more advanced form of postmodernism “hyperpostmodernism,” and in Scream, this is identified in two ways: (1) the loss of tongue-in-cheek sub-text in favor of actual text and (2) active referencing and borrowing of influential styles. The rules I quoted above are a great example of the first point, a type of discussion among characters that happens throughout the films. The dim lighting, camera angles, character names are all good examples of the second point. It’s s slasher film about slasher films, if you will. It worked so well because it acknowledged and played to the media hyperconsciousness of the American teenagers of that generation. As Wee puts it, a group that is “media literate, highly brand conscious, consumer oriented, and extremely self-aware and cynical.” Now doesn’t that make us sound like lovely people?

As this hyperconscious generation, we can look back at the conventions, ideologies, and representations of those past works. We can ask what the attributes and associated tropes are of a successful horror movie. To do that, let’s go back to a 1991 paper by Douglas Rathgeb. In it, he identifies one of the most effective attributes of a horror film to be the unsettling sense of intrusion it creates, that feeling of normal versus abnormal. It is true that we must separate movie reality from real life but in the case of horror movies, the shock of the sudden, often freakish, intrusion of the horror to be a terrifying element whether it is the perception of the reality or the acts of a bogeyman (or both). This unnerving feeling is evident in A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) in which Wes Craven creates a nightmare state coexistent with reality. He removes the conventional signposts and distorts the physical parameters that we use to measure reality. Rathgeb spends a good amount of time on the id/superego model (specifically the “bogeyman id”) that I won’t go into, but he continually draws on the point of the victims’ moral blemish – the Original or Unpardonable sin – that permits some evil to terrorize the world. Randy’s first Rule plays out in Freddy Krueger’s increasingly disturbing, nocturnal, murderous visits upon the sexually active teenagers of Springwood. It is also exemplified in Michael Myers’ first murderous act in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), the act that leads him down the path of transformation into the bogeyman that menaces the morally deficient residents of Haddonfield.

As this hyperconscious generation, we can look back at the conventions, ideologies, and representations of those past works. We can ask what the attributes and associated tropes are of a successful horror movie. To do that, let’s go back to a 1991 paper by Douglas Rathgeb. In it, he identifies one of the most effective attributes of a horror film to be the unsettling sense of intrusion it creates, that feeling of normal versus abnormal. It is true that we must separate movie reality from real life but in the case of horror movies, the shock of the sudden, often freakish, intrusion of the horror to be a terrifying element whether it is the perception of the reality or the acts of a bogeyman (or both). This unnerving feeling is evident in A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) in which Wes Craven creates a nightmare state coexistent with reality. He removes the conventional signposts and distorts the physical parameters that we use to measure reality. Rathgeb spends a good amount of time on the id/superego model (specifically the “bogeyman id”) that I won’t go into, but he continually draws on the point of the victims’ moral blemish – the Original or Unpardonable sin – that permits some evil to terrorize the world. Randy’s first Rule plays out in Freddy Krueger’s increasingly disturbing, nocturnal, murderous visits upon the sexually active teenagers of Springwood. It is also exemplified in Michael Myers’ first murderous act in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), the act that leads him down the path of transformation into the bogeyman that menaces the morally deficient residents of Haddonfield. This segues nicely into a discussion of misogyny, the male monster, and the Final Girl. You don’t have to be a film expert to notice that slasher films contain a lot of violence primarily directed toward women, usually after they have broken Randy’s first Rule. In 2010 in the Journal of Popular Film and Television, Kelly Connelly studies this closely. She examines a marked change in the structure and action of horror films in the mid-1970’s, the birth of the slasher film subgenre. Within this subgenre a new role emerged: the Final Girl, the sole female survivor of a rampaging psychotic who has managed to rescue herself. You will know her when you see her in the beginning of the movie as she is the Girl Scout, the bookworm, the mechanic, the tomboy. She probably has a male name, isn’t sexually active, is resourceful, and is watchful to the point of paranoia. Connelly spends most of the paper breaking down Halloween and Halloween H2O: Twenty Years Later. I don’t have the space to cover all of that here, but ultimately, the Final Girl character boils down to one word: empowerment. The female victim achieves active empowerment through the act of rescuing herself.

This segues nicely into a discussion of misogyny, the male monster, and the Final Girl. You don’t have to be a film expert to notice that slasher films contain a lot of violence primarily directed toward women, usually after they have broken Randy’s first Rule. In 2010 in the Journal of Popular Film and Television, Kelly Connelly studies this closely. She examines a marked change in the structure and action of horror films in the mid-1970’s, the birth of the slasher film subgenre. Within this subgenre a new role emerged: the Final Girl, the sole female survivor of a rampaging psychotic who has managed to rescue herself. You will know her when you see her in the beginning of the movie as she is the Girl Scout, the bookworm, the mechanic, the tomboy. She probably has a male name, isn’t sexually active, is resourceful, and is watchful to the point of paranoia. Connelly spends most of the paper breaking down Halloween and Halloween H2O: Twenty Years Later. I don’t have the space to cover all of that here, but ultimately, the Final Girl character boils down to one word: empowerment. The female victim achieves active empowerment through the act of rescuing herself.But are women really slasher film victims more often than men, or is it just more noticeable? A 1990 study by Cowan and O’Brien asked participants to analyze 56 slasher films to see how female and male victims survived as related to several traits, including markers of sexual activity (clothing, initiation, etc.). They found that women were neither more likely to be victims of slashers nor less likely to survive when attacked. In fact, they were more likely to survive than men. The authors postulate that this perception is likely because of the female victims in memorable films/scenes, especially when sex is involved, and that the female status in society as someone to be protected makes their victimization all that more evident. They also found that the non-surviving females were more frequently sexual, physically attractive, and inane. Randy got it right on that one. Non-surviving males tended to be assholes (my term, not theirs) in that they had bad attitudes, engaged in illegal behaviors, and were cynical, egotistical and dictatorial. Notice that whether or not they broke the first Rule is not included.

A 2011 paper by Richard Nowell argues that although early teen slasher (and/or stalker) films were made primarily for male youth, the marketing campaigns were also geared toward young women. Keep in mind that Nowell is not asking you focus on the nonviolent content and the films’ promotional campaigns. He asks you to consider movies like My Bloody Valentine (1981) and Prom Night (1980) which had posters picturing teens slow dancing beneath decorative hearts and tag lines like “There’s more than one way to lose your heart.” Even A Nightmare on Elm Street billed the principle protagonist as “she’s the only one who can stop it – if she fails, no one will survive.” Movies like Prom Night and Carrie (1976) spotlight female protagonists, female bonding, and various courtships. These tactics can been seen throughout the genre and even into their contemporary remakes.

On the topic of remakes, in 2010, a paper by Ryan Lizardi compares the original movies to their remakes to see how they relate and how they speak to current cultural issues. Slasher movie remakes tend to stem from a particular period, the 1970’s through the early 1980’s, a period known for its ideological issues with gender and political ambivalence. There are quite a few anti-remakers that take the view that the original is better partly because they are best understood in relation to the periods in which they were produced. Remakes often have to redefine normal vs. abnormal to fit a contemporary time. Also, to fit the new time, the rules have changed, trending towards more gore and stylized production. Lizardi goes through the details, but Scream 4 boils down the Rules to successfully survive a horror movie remake: (1) death scenes are way more extreme, (2) unexpected is the new cliché, (3) virgins can die now, (4) new technology is now involved…cell phones, video cameras, etc., (5) don’t need an opening sequence, (6) don’t f- with the original, and (7) if you want to survive, you pretty much have to be gay. Okay, so maybe Lizardi doesn’t say the last one. He does spend some time revisiting the remake of the Final Girl. Remakes often have this character learn and witness the full extent of the killer’s depravity (in a really gory way) and endure the most psychological damage. Lizardi concludes that these films speak to contemporary concerns and even have endings.

Let’s turn our head to sequels, 'cause let's face it baby, these days, you gotta have a sequel. A 2004 paper by Martin Harris examines the horror franchise. He draws on the concepts of postmodernism and the unsettling feeling of normal vs. not-normal. Why do the killers – Freddy, Michael, Jason – keep coming back? He argues that their resurrection in sequels engenders its own frightening uncertainty. Where is the threshold? When is dead really gone? Harris spends a good deal of time arguing that it is more the economic realities of Hollywood that drive the sequel-making process rather than a demand from moviegoers to revisit the killers. I can see a lot of truth in that as these are known properties that have relatively small budgets. But sequels also come with expectations. The author points out the case of Halloween III: Season of the Witch. You probably go into this movie expecting to see Michael Myers. Not so. Instead you end up with a weird children’s costume related plot. But, I guess these days we are much more likely to see a remake than a Halloween 12. Or even a prequel.

Let’s turn our head to sequels, 'cause let's face it baby, these days, you gotta have a sequel. A 2004 paper by Martin Harris examines the horror franchise. He draws on the concepts of postmodernism and the unsettling feeling of normal vs. not-normal. Why do the killers – Freddy, Michael, Jason – keep coming back? He argues that their resurrection in sequels engenders its own frightening uncertainty. Where is the threshold? When is dead really gone? Harris spends a good deal of time arguing that it is more the economic realities of Hollywood that drive the sequel-making process rather than a demand from moviegoers to revisit the killers. I can see a lot of truth in that as these are known properties that have relatively small budgets. But sequels also come with expectations. The author points out the case of Halloween III: Season of the Witch. You probably go into this movie expecting to see Michael Myers. Not so. Instead you end up with a weird children’s costume related plot. But, I guess these days we are much more likely to see a remake than a Halloween 12. Or even a prequel.Whew. Have we covered everything? I think so. I tried to keep things general, talking mostly about major concepts that I hope got you thinking. If you like a particular topic then I encourage you to find the paper as they are all pretty good reads. And let me know your thoughts in the comments.

The references are, in order of their appearance:

Rathgeb, Douglas L. (1991). Bogeyman from the ID: Nightmare and Reality in Halloween and A Nightmare on Elm Street Journal of Popular Film and Television, 19 (1), 36-43 DOI: 10.1080/01956051.1991.9944106

History of Horror Films:

Horror Film History

Filmmaker IQ’s “A Brief History of Horror”

AMC filmsite’s “Horror Films”

The Cinephile Fix’s “The Roots and History of the Horror Film”

No Film School’s “From Nosferatu to Jigsaw: a Look at the History of Horror Films”

Oh, and it's worth a visit to the Final Girl blog too!

(image via Scream Wiki)

Thursday, October 23, 2014

Trick-or-Treating: What Do You Hand Out On Halloween?

Halloween is almost here. And you know what that means: Candy! It’s one of those Halloween traditions that I just never seem to have grown out of. Those little chocolate bars are seriously dangerous to my waistline. Remember how much Halloween candy you ate when you were a kid? Were you one of those kids who gorged on all that sugary goodness, or were you the type to parse it out and make it last? I was a Trader, that kid that made deals to trade all her bad candy for the good stuff. Anyway, the topic of Halloween candy got me to searching through the scholarly journals in search of an article for today’s post. I came across a paper that asks if children really need all of that candy on Halloween. My first instinct was “Of course they do! It’s Halloween!” But, well, read on…

It seems that being a fat American isn't just limited to adults, childhood obesity has been on the rise over the last 3 to 4 decades. Access to unhealthy foods and the poor nutritional quality of their diets is much to blame for this. The promotion and glorification of high sugar, high fat foods on Halloween is simply a good example. It probably comes as no surprise that research has shown that when children are given free access to tasty food that they eat it, especially if it’s sweet, even when they are not hungry. But is there a good alternative that kids will like? A slightly older paper published in Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior investigated the option and value of nonfood treats as substitutes for candy on Halloween.

To do this, the researchers gave 284 trick-or-treating children a choice of a toy or candy. The toys included stretch pumpkin men, large glow-in-the-dark insects, Halloween theme stickers, and Halloween theme pencils. The candy choices were recognizable name brand lollipops, fruit-flavored chewy candies, fruit-flavored crunchy wafers, and “sweet and tart” hard candies. All of these toy and candy options ranged between 5 and 10 cents per item. When a trick-or-treating child arrived at a door, they were asked for their age, gender and a description of their Halloween costume (pretty typical…except maybe the gender question). Then they were presented with 2 identical plates: 1 with 4 different types of toys and the other with 4 different types of candy, alternating by site/household which on side the plates were located. Only children between 3 and 14 were included. And, if the child asked for both toy and candy, they were allowed to take both but were excluded from the study, but only 1 little girl did that.

The results of the study showed that children chose toys as often as they chose candy. This suggests that children may forego candy more readily than adults expect. The authors cite Social Cognitive Theory as providing a way for candy alternatives to become more commonplace. According to this Theory, when parents see that children are accepting the candy alternatives they are more likely to continue the new toy giving behavior. Factor in the other fun Halloween activities – dressing up, walking around the neighborhood at night, etc. – and these toy treats become positively associated with the fun and the holiday.

Okay, so what about the Halloween-only-comes-once-a-year argument. I’ll admit it is a good one and it something that the authors spend time to address. They point out that Halloween isn’t the only holiday where food and candy are advertised. Well, isn’t that the truth. They even make a nice list of other food laden holidays and events: weddings, new babies, graduation, back-to-school, birthdays, Christmas, Hanukkah, Valentine’s Day, Easter, St. Patrick’s Day, Cinco de Mayo, Earth Day (wait…you get food on Earth Day?), Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, and Independence Day. What they don’t add in are all of the other food-filled events that come seasonally (picnics, cook-outs, etc.) and socially (happy hours, get-togethers, etc.). Put together, that’s a lot of bad food choices all year long.

Ultimately, what the authors are getting at is promoting healthy choices throughout the year. Part of this is giving children healthier options and traditions. It is almost more of a change for adults than it is for children. Breaking those food habits and associations isn’t easy, y’all. Food isn’t love, no matter how many Hershey’s Kisses you give someone. Wow did that ever sound shrinky!

But I’ll throw in a last little note that I think almost every child on the planet would agree with: Don’t be that house than hands out toothbrushes.

(image and product via epicurious)

Monday, August 25, 2014

Spoiler Alert!: Are You Wasting Your Time Avoiding Spoilers?

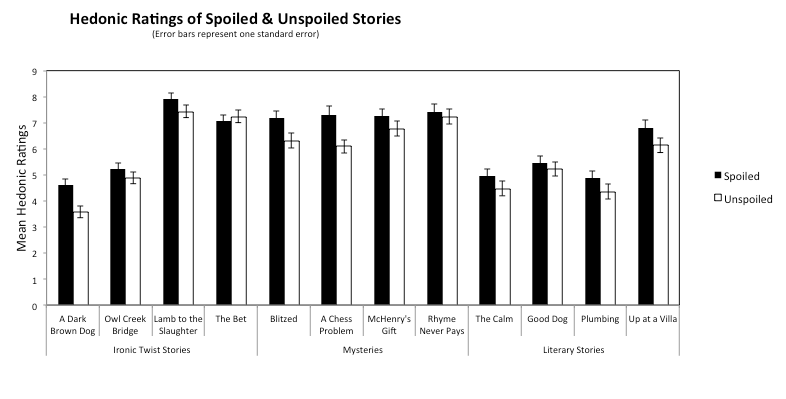

In 2011, a short little study published in Psychological Science by Leavitt and Christenfeld asked if spoiling a story decreased peoples’ pleasure in it. The universal element of all types of media is story. When you talk about spoilers you are inherently talking about changing someone’s enjoyment of the story. The study asked 176 males and 643 females (just a little sex biased and not broken down by any other demographics) to take part in three experiments in which they read three different sorts of short stories selected from anthologies: (1) Ironic-twist stories, (2) Mysteries, and (3) Evocative literary stories. For each of the stories, some of the participants’ stories included a spoiler paragraph that summarized the story and gave the outcome. Afterwards, the participants were asked to rate the story for enjoyment on a 10 point scale – a “hedonic rating.” They found that the participants significantly preferred spoiled over unspoiled stories in all categories and reported that the spoiler paragraph was not out of place or jarring.

|

| Figure 1 from the study. These are hedonic ratings of the individual spoiled and unspoiled stories. |

Considering all of the attention this study got when it was published and the applications made to a variety of media, I’m going to throw in a little more personal critique than I do normally. Start out by asking: Are their data wrong? Well, no. But there are some methodologies and assumptions that I question. They assume that I have the same experience each time I read a story. The authors do focus on that first reading but also state that “people’s ability to reread stories with undiminished pleasure, and to read stories in which the genre strongly implies the ending, suggests that suspense regarding the outcome may not be critical to enjoyment and may even impair pleasure by distracting attention from a story’s relevant details and aesthetic qualities.” As someone who rereads her favorite books over and over again, I say “not so!” Their statement suggests that I did not enjoy the shock of a scene the first time around when in fact I did. You know what I mean: that “holy-crap-did-that-just-happen?!!!” moment. Am I saying that twist is all there is? Of course not, but one of the memorable parts of the first reading - the surprise - would not have been the same without it. Upon rereads, my undiminished pleasure comes from the writing and spending more time in a world with characters that I love (or love to hate).

The study’s authors conclude that “people are wasting their time avoiding spoilers,” but go on to say that that their data “do not suggest that authors err by keeping things hidden.” They point out that readers who read stories that open with the outcomes still anticipate additional revelations at the end. To me, this statement suggests that readers still expect twists in the story even though they've just read all of them, that they are waiting for the shock, the twist. A good example might be someone who is seeing a film adaptation of a book they've read; they are looking for the differences in the movie. Considering this, I think would have liked more detail in the methods about how their spoilers were presented. I wonder if a big “Spoiler Alert” warning on that summary paragraph would have made a difference – one that labeled and explained it as something that spoiled everything. Perhaps this would remove this erroneous anticipation? Or what about a before questionnaire that scored anticipation levels? Personally, I am way more upset if someone spoils something I've been looking forward to compared to something I could care less about. What about gauging viewpoints on spoilers by asking a simple question like: Do you read the last chapter of a book first to see what happens?

Did I come into this paper with some preconceived notions? Sure, but I seem to have more problems with this study than most. Upon reflection, I think that stems from problems I have with the study's methodology added to the attention it has gotten (it hasn't escaped me that I’m giving it even more with this post). It has been used to justify spoiling a story – a behavior that I typically find to be one of smug superiority. I think it is important to keep in mind that this is a single small study, and one that had I been a reviewer for would have gotten hacked to pieces. I'm a fan of a nice, simple study but I'm not a fan of lack-of-detail, particularly in the methods.

But I'm not a psychologist, what do I know? What do you think? Do you love or hate spoilers? How would you have done a study on this topic?

Here's some of the media attention this study received and a couple other articles on the topic. Spoiler Alert - some of these contain spoilers.

Film School Rejects: "How Bad Do Spoilers Spoil?: A Super Scientific Study

Smithsonian: "Are Spoilers Misnamed?"

UC San Diego News Release: "Spoiler Alert: Stores Are Not Spoiled by 'Spoilers'"

/Film: "Spoilers Are Good For You, Says Study"

The Atlantic: "Here's the Twist: Good Films Are Good Even If They've Been 'Spoiled'"

io9: "The Cultural Curse of Knowledge and Movie Spoilers"

io9: "Why I refuse to watch movies without spoilers"

Vulture: "Spoilers: In Defense of the American Watercooler"

Vulture: "Spoilers: The Official Vulture Statutes of Limitations" (I like this proposes a stature of limitations on spoilers based on the media type)

Techie.com: "Spoiler Alert: A Survival Guide to All Things" (also the source of the image)

Labels:

behavior,

humans,

movies,

psychology,

sociology

Monday, November 25, 2013

Going to the Movies: The Seat Choice Dilemma (Part 3)

Welcome to Part 3, the final step in our science-tastic trip to the movie theater. I’d suggest checking out Part 1 and Part 2 as so far, you've purchased your expensive ticket, wondered at high concession prices, agonized over which size popcorn to buy, and learned how that choice will ultimately determine how much you will eat. Now you are ready to go find a seat for the show! You pick up your concessions from the counter, figure out how to carry them in such a way as to not spill anything and yet still be able to hand your ticket to be torn, walk down the hallway to find your theater number, go down the dark felt-covered tunnel, and then stand at the bottom of the stairs contemplating which row to sit in.

Let’s start by asking if where you sit will really affect what you see? There is an older, interesting piece written by James Cutting in 1986 that looks at the shape and psychophysics of cinematic spaces. Probably haven’t heard the term psychophysics, right? I know I hadn't. Well, it is a branch of psychology that’s concerned with how physical processes (the intensity of stimulants like vision and sound) affect your sensations, perceptions, and mental processes. Basically, a mind-body problem. Movies have the capacity to draw us in such that we get “lost” in them; we project ourselves into a new space and time, one that the filmmakers have created for us. The high picture quality and larger screens have been shown to help give us viewers the impression of “being there.” Dimming the lights dims out the real world, the large screen fills our optic array, the smoothness of the frame rate (flicker threshold) allows the images we see to become lifelike, and the pacing of scenes and cuts can enhance our emotions. However, a movie is ultimately an optical projection and it would be logical to think that where you sit may matter in how you see the movie (geometry, distortions, etc.). But in his paper, Cutting describes why this isn't so. He uses static art as an example, asking you to look at a picture from different angles. Then he explains that affine and perspective transformations affecting the look of rigidity of objects on the screen is actually very difficult for people to discern (what he terms La Gournerie’s paradox). In search of why this is so, he goes through a lot of history, and geometry, and equations, and well, I’m not even gonna touch those. But essentially, he comes down to two possibilities: (1) our brains compensate for and rectify any distortions we see by using information about screen slant, and (2) we preserve information about the transformations we see to ensure our perception remains unperturbed. So when you’re standing at the bottom of those stairs looking around for a seat, know that where you sit doesn't really matter in how you view the movie. Your brain’s got it covered.

Choosing a seat, however, is a conscious choice. Like any other choice it is influenced by the characteristics of the item, particularly (and especially in this case), the location. Let’s start simple and consider our lateralized tendencies, a.k.a. which side of the theater you like to sit on, right or left. A study published in Cortex in 2000 looked at handedness as a predictor of behavioral asymmetries. Previous studies of cerebral organization show that the brain’s right hemisphere shows a considerable advantage for face recognition, spatial stimuli, and emotions. With this knowledge, this study asked if these directional biases are reflected in the seat choices we make at the cinema. The researchers screened and interviewed participants for handedness (right, left, mixed). Then they gave them maps of five theaters, each differing in the location of the entries/exits and aisles, and dividing seats into equal parts with the middle seats marked as sold out. They found a preference for right positions when watching movies in the three handedness classes underlying a left-directed perceptual bias, which they found to be most evident in right handers and decreased progressively from them to the left handers. The author postulates that this is because the leftward orientation of attention fosters the activation of the right hemisphere cultivated through the learned reflexes of previous biases. A study published in Laterality in 2006 also looked at this seat-side preference, also by asking participants to look at various maps of theater seating, this time altering screen location. This study confirmed the overall right side seat preference, with a stronger preference if the screen were at the top or right of the map, and additional preference for seats at the back of the cinema. However, they found that the turn at the entrance to the theater to perfectly correlate with the chosen seat-side. A result that could reflect general turning habits (I really hope that someone has termed this the Zoolander Hypothesis).

I think we can all agree that handedness is a rather simple way to look at something. There is obviously more going on here. A paper, this time in Applied Cognitive Psychology in 2010, added the role of motivation to their study. They wanted to know if people highly motivated to see a movie would choose the right side of the theater, since these seats are better suited to processing information from the left visual field and therefore direct access to the visual and emotional side of the brain (right hemisphere). In their first experiment they told all of the participants that a movie was highly recommended and half of them were further advised that they would rather avoid watching the movie because the story was sad and depressing (thereby negating the positive motivation of the recommendation while also giving negative motivation). Then they asked the participants to choose a seat from a seating chart. Knowing that some dark or depressing stories often achieve immense commercial success (e.g. The Dark Knight), they also conducted an experiment where they reversed the status of the negative emotional content. They found that when right-handers were positively motivated they chose seats on the right side. This bias disappeared when they were negatively motivated. This held true even when a depressing movie was spun a positive. Non-right-handers did not exhibit such lateral biases regardless of experimental condition.

Personally, I’m a middle theater, middle seat kind of person. That particular bias hasn't really been addressed by the studies above, in fact they grey-out the middle seats to force people to choose a side. This is what Rodway et al. considered when they conducted their study in 2012. They decided to compare the right-side preference to the center-stage effect. The latter suggests that people’s choice decisions are guided by the perception that good, important people occupy the middle. They examined this closer in a first experiment where they presented people with five identical pictures (of random regular things like butterflies or waterfalls) arranged in a line and asked them to pick their most and least preferred items. The results showed a significant trend for people to select their most preferred item in the middle position, a result not seen when choosing the least preferred item. A second experiment looked at the array format to see if the center tendency extended to vertically arranged items, knowing that top positions are generally associated with positive attributes and vice versa. As with the first experiment, participants chose items in the center rather than the top or bottom, adding robustness to this center-stage theory. A final experiment wanted to see if these preferences are associated with real items rather than just pictures. As with the other two, this experiment showed a preference for center items, although there was also a significant reduction for the items at the lowest two locations. Did they actually go into a theater and ask people about seats? Well no. But I included this study because I have yet to come across a paper that has asked this, and being a center-seater, I thought it was a rather important aspect to the whole seat-choice dilemma.

These studies all look at a simple choice aspects, which, admittedly, is a good place to start. However, I think I would like to read about how group size matters. You know you ask your friends where they want to sit, right? Or what about how people don’t like to sit next to each other? What about choosing a seat in a theater where many of the seats are already taken? If your preferred seats are gone, where do you sit?

Well, that’s all for our trip to the cinema. Now that you've found your seat, enjoy the show!

(image via The Expert Institute)

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

Going to the Movies: The Story of a Popcorn Pit (Part 2)

Welcome to Part 2 of my journey to the movie theater. This will make sense if you haven’t read Part 1, but to enjoy the full impact of this visite du cinéma, I suggest you read both. If ya just don’t wanna then here’s a summary: (1) movie tickets are expensive, (2) as far as I can tell, nobody has really done a direct study of why, (3) economists try to explain why all movies cost the same through their “uniform pricing for differentiated goods” theory, (4) as it turns out, variable or differentiated pricing is probably better, (5) concessions are expensive too, (6) theaters get all of this “consumer surplus,” (7) channels of ticket distribution, group size, and theater characteristics affect concession sales, and (8) theaters get as much money as possible from people willing to pay it.

So far, we've made it past the door with our high priced tickets, and we stood in front of the concession stand wondering why those prices are also so high. Let’s say that you decide to take the monetary plunge and buy some concessions. You look over the candy, the nachos, the questionable looking hot dogs and you decide to go with popcorn. You look at the sizes of the containers, perhaps ask to see one a little closer, and go with the medium. But wait! The large is only 25 cents more! Okay, so you go with the large. I mean, if you are going to pay 5 dollars for popcorn then there might as well be a lot of it right?

What are the effects of ordering that 18 cup bucket of inflated food? It is slathered in a buttery goodness that makes it pretty frickin’ yummy, but are you really going to eat all of that? Most people tend to think that how much they eat is based on the taste of the food. Studies in the absence of environmental cues have largely shown this to be true. That makes sense if you think about it. When you have no distractions you can concentrate on the flavor of your food. However, the movie theater is the opposite of a distraction-free environment.

In 2001 Wansink and Park published a study where they gave 161 moviegoers free popcorn and soft drinks. The same popcorn was given in either a medium (120g) or large (240g) container, with before and after weights taken to see how much was eaten. Then they asked the participants to fill out a questionnaire after their movie about the taste of the popcorn. The results showed that people who rated their popcorn as tasty ate 49 percent more if it was in a large container than a medium one. Surprisingly, people who rated the taste of their popcorn as unfavorable still ate 61 percent more if it was put in a larger container. A related study from 2005, also headed by Wansink, looked at how container size can influence food intake, even when it is less palatable. Again they randomly gave 158 moviegoers either a medium or large container of popcorn, weighing the containers before and after the movie. But this time they purposefully changed the taste of the popcorn, giving participants either fresh or stale (14 days old…eww). Similar to the first study, the results showed that moviegoers ate 45.3 percent more popcorn from a large container than from a medium container when the popcorn was fresh. And while the moviegoers with stale popcorn negatively described their food as “stale,” “soggy,” or “terrible,” they still ate 33.6 percent more if they were given large containers than if they were given medium containers.

A more recent study published in the journal Appetite also looked to see if people consumed more food with larger containers, this time focusing on portion size vs. container size. They served M&M’s for free to 88 undergraduate students watching a 22 minute long TV show. Participants were served either a medium portion of M&M’s in a small container, a medium portion in a large container, or a large portion in a large container. Given the same amount of food, people with the large containers ate 129 percent (199 kcal) more than people with the medium containers, and when given a larger portion size they ate 97 percent more. Basically, that large bucket of food stimulates your food intake over and above the portion size. So perhaps that large popcorn you purchased wasn't the best idea.

But fear not! There is actually an up-side. You know how you eat most of your popcorn before the movie even starts, during the ads and previews? Well, an article published online this year in the Journal of Consumer Psychology looked at how “oral interference” (i.e. eating) affects the impact of those ads on people’s brand attitudes and choices. In their experiments, they gave free popcorn and chewing gum to participants and asked them to watch a movie preceded by a series of real but foreign commercials (so they hadn't seen them before), asking them to eat as soon as the commercials started. Then one week later they assessed the participants and a control group (no free popcorn or gum) for their purchasing choices. The researchers found that the control group spent more money and had a preference for the brands they saw in the commercials. The participants that ate during the commercials showed no such preferences. Yeah! Pop blocked!

I’ll see you next week for the last, and final, part of this series. Happy eating!

Just for interest’s sake, an interesting article from the Smithsonian about the history of popcorn and the cinema: "Why Do We Eat Popcorn at the Movies?"

(image via birthdayexpress.com)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)