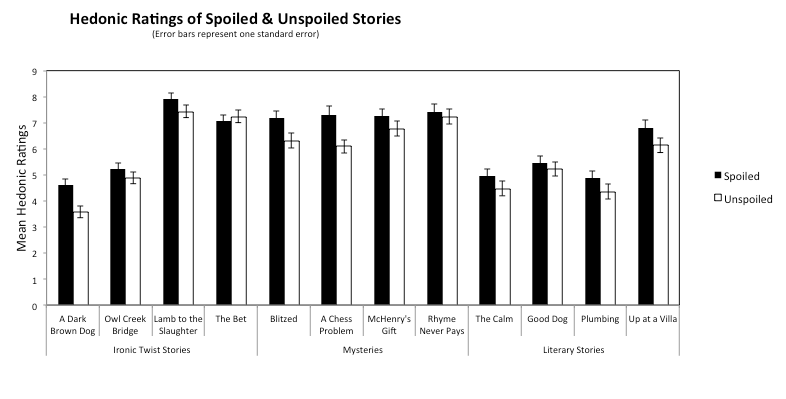

In 2011, a short little study published in Psychological Science by Leavitt and Christenfeld asked if spoiling a story decreased peoples’ pleasure in it. The universal element of all types of media is story. When you talk about spoilers you are inherently talking about changing someone’s enjoyment of the story. The study asked 176 males and 643 females (just a little sex biased and not broken down by any other demographics) to take part in three experiments in which they read three different sorts of short stories selected from anthologies: (1) Ironic-twist stories, (2) Mysteries, and (3) Evocative literary stories. For each of the stories, some of the participants’ stories included a spoiler paragraph that summarized the story and gave the outcome. Afterwards, the participants were asked to rate the story for enjoyment on a 10 point scale – a “hedonic rating.” They found that the participants significantly preferred spoiled over unspoiled stories in all categories and reported that the spoiler paragraph was not out of place or jarring.

|

| Figure 1 from the study. These are hedonic ratings of the individual spoiled and unspoiled stories. |

Considering all of the attention this study got when it was published and the applications made to a variety of media, I’m going to throw in a little more personal critique than I do normally. Start out by asking: Are their data wrong? Well, no. But there are some methodologies and assumptions that I question. They assume that I have the same experience each time I read a story. The authors do focus on that first reading but also state that “people’s ability to reread stories with undiminished pleasure, and to read stories in which the genre strongly implies the ending, suggests that suspense regarding the outcome may not be critical to enjoyment and may even impair pleasure by distracting attention from a story’s relevant details and aesthetic qualities.” As someone who rereads her favorite books over and over again, I say “not so!” Their statement suggests that I did not enjoy the shock of a scene the first time around when in fact I did. You know what I mean: that “holy-crap-did-that-just-happen?!!!” moment. Am I saying that twist is all there is? Of course not, but one of the memorable parts of the first reading - the surprise - would not have been the same without it. Upon rereads, my undiminished pleasure comes from the writing and spending more time in a world with characters that I love (or love to hate).

The study’s authors conclude that “people are wasting their time avoiding spoilers,” but go on to say that that their data “do not suggest that authors err by keeping things hidden.” They point out that readers who read stories that open with the outcomes still anticipate additional revelations at the end. To me, this statement suggests that readers still expect twists in the story even though they've just read all of them, that they are waiting for the shock, the twist. A good example might be someone who is seeing a film adaptation of a book they've read; they are looking for the differences in the movie. Considering this, I think would have liked more detail in the methods about how their spoilers were presented. I wonder if a big “Spoiler Alert” warning on that summary paragraph would have made a difference – one that labeled and explained it as something that spoiled everything. Perhaps this would remove this erroneous anticipation? Or what about a before questionnaire that scored anticipation levels? Personally, I am way more upset if someone spoils something I've been looking forward to compared to something I could care less about. What about gauging viewpoints on spoilers by asking a simple question like: Do you read the last chapter of a book first to see what happens?

Did I come into this paper with some preconceived notions? Sure, but I seem to have more problems with this study than most. Upon reflection, I think that stems from problems I have with the study's methodology added to the attention it has gotten (it hasn't escaped me that I’m giving it even more with this post). It has been used to justify spoiling a story – a behavior that I typically find to be one of smug superiority. I think it is important to keep in mind that this is a single small study, and one that had I been a reviewer for would have gotten hacked to pieces. I'm a fan of a nice, simple study but I'm not a fan of lack-of-detail, particularly in the methods.

But I'm not a psychologist, what do I know? What do you think? Do you love or hate spoilers? How would you have done a study on this topic?

Here's some of the media attention this study received and a couple other articles on the topic. Spoiler Alert - some of these contain spoilers.

Film School Rejects: "How Bad Do Spoilers Spoil?: A Super Scientific Study

Smithsonian: "Are Spoilers Misnamed?"

UC San Diego News Release: "Spoiler Alert: Stores Are Not Spoiled by 'Spoilers'"

/Film: "Spoilers Are Good For You, Says Study"

The Atlantic: "Here's the Twist: Good Films Are Good Even If They've Been 'Spoiled'"

io9: "The Cultural Curse of Knowledge and Movie Spoilers"

io9: "Why I refuse to watch movies without spoilers"

Vulture: "Spoilers: In Defense of the American Watercooler"

Vulture: "Spoilers: The Official Vulture Statutes of Limitations" (I like this proposes a stature of limitations on spoilers based on the media type)

Techie.com: "Spoiler Alert: A Survival Guide to All Things" (also the source of the image)

No comments:

Post a Comment